“We never know the worth of water until the well is dry.”

In the four seconds it took to read that famous quote by Thomas Fuller, about 200,000 liters of water had been released from Angat Dam. This amount is sufficient to cover a day’s worth of water needs for more than 1,300 people (300 households) in Metro Manila.

However, rising temperatures over the past decade, intensified by extreme weather events such as El Niño, have caused Angat Dam’s water elevation to go down to the minimum operating level during the dry season. This poses a significant threat to water security in Metro Manila and the communities surrounding Angat Dam as the demand for water increases as people continue to flood into the capital region.

In this four-part series, ABS-CBN News examines Metro Manila’s precarious dependency on Angat Dam for most of its water requirements, how El Niño and climate change wreaked havoc on its ability to supply water, who bears the brunt of past and future water shortage, and the importance of governance and citizens participation to address the issue.

Part 1: Millions of people and one source of water

“Water is our lifeline. We can do without electricity, but not a single day without water," said Elsa Cabrellas, 57, as she recalled her experience when water interruptions were implemented in their community back in 2019. The household didn't have water—not a single drop from the tap—for a week.

The family of nine at that time had to be content with the water supplied by firetrucks deployed by the barangay. Elsa was thankful since their home, which also houses her small sari-sari store, is adjacent to the barangay hall, providing her with better access to the rationed water. She cannot imagine how challenging it must have been for other residents who had to queue during rationing schedules, especially those living in elevated areas.

As a mother of seven, Elsa had to ensure that her children had a supply of water for bathing before heading to class, in addition to the family’s basic water needs like cooking, laundry, and cleaning. Water for drinking had to be bought from water stations. She thinks it is safer for her family to drink filtered water and will prevent them from getting sick.

When the 2019 water crisis struck, about half of Metro Manila lost some access to water, according to the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System, the government agency responsible for regulating water services in the metropolis. The heavy dependence on a single source of water made it impossible to maintain a steady supply.

Manila Water’s miscalculation stemmed partially from relying on new technology aimed at improving water distribution, according to MWSS Chief Regulator Patrick Ty. “It was a governance issue, a mistake made by Manila Water, and they admitted it. They allowed the water level in La Mesa Dam to fall below the minimum operating level because they had backup plans, but they didn’t work. All their Plans A-C did not work, that’s why we had a water crisis,” said Ty.

Even with better modeling for fair water distribution, they overlooked the potential impact of the lack of rain in the first quarter of that year. Decision makers from Manila Water anticipated the rain to come early, or at least on time. They continued using water without restrictions until water elevation at La Mesa Dam dropped below its normal level of 80 meters, eventually plunging to its critical threshold level of 69 meters. “They were expecting the rains to come, they said, don’t worry the rain is going to come next month, then the water kept going down, down, down until it dipped to its lowest level. It hit us in March,” Ty added.

Angat Dam, which supplies water to La Mesa, also experienced its lowest level in the past decade, dropping at 157.98 masl (meters above sea level) on June 29, 2019. However, water level in La Mesa went down considerably earlier, eventually breaching its critical threshold of 69 meters on March 11.

The mistake cost Manila Water significant penalties amounting to P1.1 billion imposed by the MWSS Regulatory Office. Approximately P534 million was directly rebated to customers, and another 600 million pesos was deducted from their new water program.

"The year 2019 was a dark period for both concessionaires because we were severely affected by El Niño The water level in La Mesa Dam dropped to its lowest level in history, reaching as low as 69 meters from its normal level of 80 meters” said Jeric Sevilla, Manila Water Corporate Communication Head, citing how El Niño impacted the operations of Manila Water as well as Maynilad.

"In 2019, our goal was to maintain a continuous 24/7 water supply to our consumers. Unfortunately, this led to a rapid decline in the dam's water level, ultimately reaching a critical point, as seen in La Mesa during that year," Manila Water added.

Dr. Philamer Torio from the Ateneo School of Government asserts that MWSS could have exercised more caution and decisiveness in their statements. With the presence of a technical team monitoring water levels, MWSS could have promptly alerted Manila Water and directed them to manage their releases accordingly. Furthermore, he contends that “if the government asserts responsibility for sourcing new water supplies, then it must ensure timely and budgeted delivery of water supply infrastructure.”

The Water for the People Network (WPN) believes that serious lapses were committed by the MWSS Corporate and Regulatory Office, as well as the National Water Resource Board, for their failure to warn people about the decreasing level of the dam. “If they had been transparent about the situation, people could have found ways to help mitigate the problem,” said Prof. Reginald Vallejos of the WPN.

The 2019 incident prompted members of WPN to call for a dialogue with MWSS and demanded for transparency and immediate action to address the water shortage. In response, MWSS committed to prevent water cuts in the future.

As the threat of El Niño looms, Metro Manila's reliance on a single water source and booming population are creating the conditions for another crisis. More and more often, the government will have to make hard decisions about how to quench the thirst of a growing city with an ever shrinking water source.

Without Angat Dam, Metro Manila has no water

Nestled in the southern part of the Sierra Madre ranges, the Angat Watershed Forest Reserve acts like a sponge, absorbing rain slowly released into the Angat River basin and the water reservoir.

The water stored in the reservoir is then utilized as a source of potable water for Metro Manila, power generation, and irrigation for farmlands in Central Luzon.

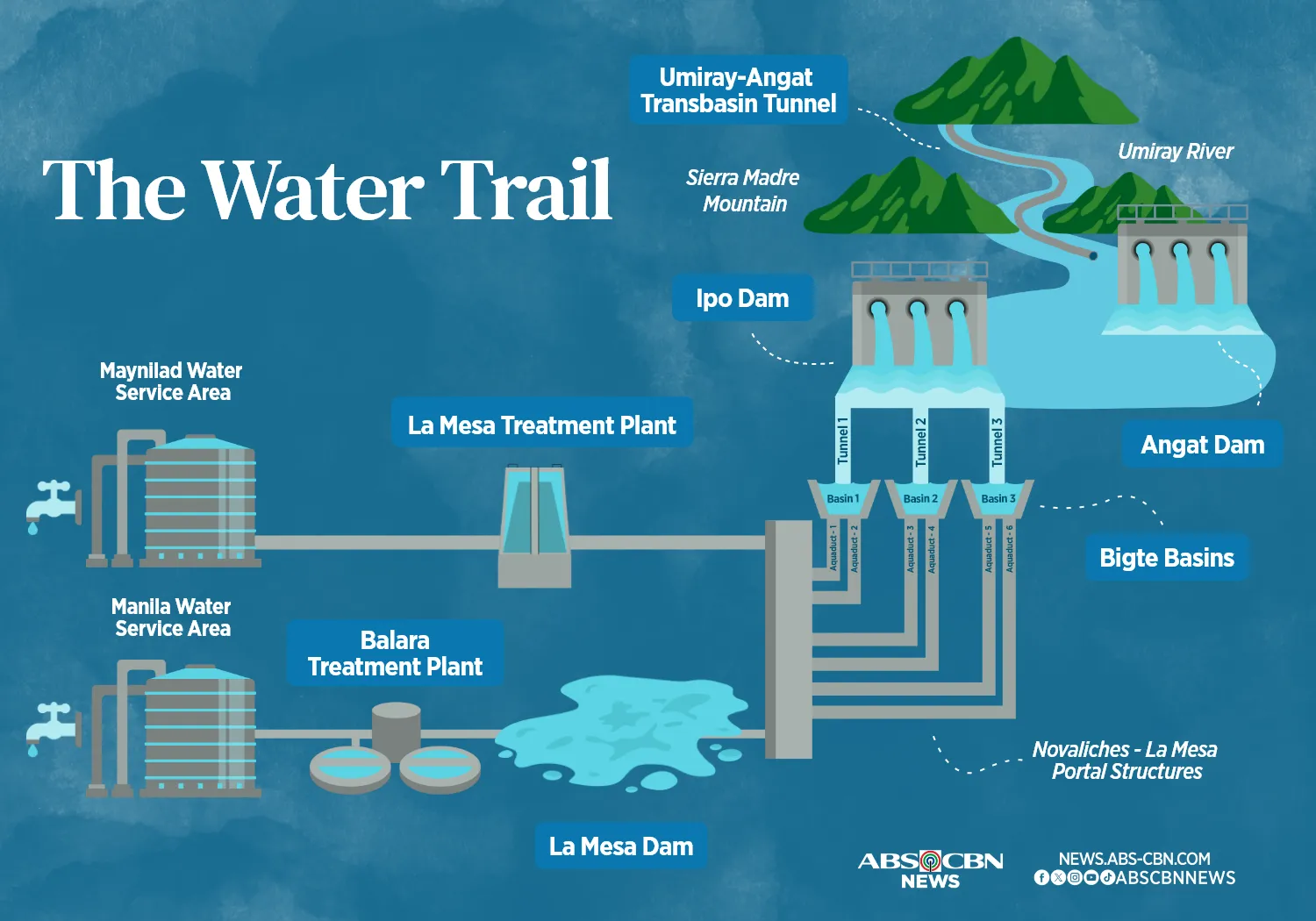

About 4,000 MLD (million liters daily) of water are released to Ipo and La Mesa dams for water treatment and distribution to customers in Metro Manila, Rizal, Cavite, and Bulacan.

According to the 2020 census, Metro Manila, with more than 13 million people, relies on Angat Dam for more than 90 percent of its water needs. Without Angat Dam, residents of Metro Manila would not have water.

Over the past decade, water levels in Angat Dam reached “the drought zone”, an alert designation when the water falls below 180 masl and below, across six separate years. At the drought zone, Angat Dam loses an amount equivalent to two out of five million cubic meters of water that Metro Manila residents consume annually. When the water level enters its drought zone, the National Water Resources Board suspends releases for irrigation to prioritize domestic consumption and power generation under its allocation protocols.

In 2019, water level in Angat Dam receded to its minimum operating level of 180 masl for 4 months beginning April 28th. The situation worsened in June, resulting in a decrease to the lower critical zone of 160 masl for more than half a month. This compelled the NWRB to reduce supply allocation from 50 cubic meters per second to 46 cms in an effort to get at least some water to residents until the rains replenished the dam. When the allocation is reduced to 46 cms, concessionaires are left with no choice but to implement supply cuts in their coverage zones to ensure that there will be enough supply while the dam awaits replenishment.

When El Niño hit the country in 2019, the water level in Angat significantly dropped from its normal high level of 212 meters above sea level (masl), declining by an estimated height equivalent to that of an 18-storey building. This decrease is twice the average drop in water level of 25 meters, akin to an 8-storey building, observed during dry seasons in the past 10 years.

The amount of water needed to fill Angat back up to its normal high water level equates to half a year's worth of water supply for Metro Manila. The lack of rain spelled disaster as it would require 3 typhoons with moderate rainfall to replenish water in the dam.

“The climate has been changing in the past few years, especially with El Niño. Generally, you try to adapt to it, then it changes again. That’s the problem. You can actually adjust to it if it does not change too fast or too frequently. The issue right now is the weather patterns change too frequently,” according to Patrick Ty of MWSS.

The unpredictability in the climate patterns has made it more challenging for agencies regulating water supply in the dam. In the next part of this series, we will investigate why water security could get worse due to a confluence of climate factors.

Part 2: Climate forces and their looming impact on Metro Manila’s water supply

Water, a vital resource for human survival, has become scarce in parts of the globe in the face of climate change. Manila faces a dangerous combination of unpredictable factors that make it especially vulnerable. Rising temperatures and below-normal rainfall, even without extreme weather events like El Niño, have diminished the environment's capacity to replenish water as efficiently as before.

The rising temperatures over the past decade, intensified by extreme weather events such as El Niño, have caused Angat Dam to breach minimum operating levels during the dry season. Climate change and El Nino are pushing Angat Dam to crisis point more and more often with the government forced to make potentially life and death decisions about who gets water and who doesn’t.

According to Ms. Ana Solis, head of PAGASA’s Climate Monitoring and Prediction Section (CLIMPS) Climatology and Agrometeorology Division, local warming is the new normal and gets worse during El Niño periods. The effects of ocean temperature warming are more noticeable during El Niño due to higher sea surface temperatures. But even without El Niño or La Niña, Manila is getting hotter and the dam is getting drier.

Mean temperature increases of at least 0.68 degrees Celsius to as high as 1 degree Celsius were recorded at three weather stations near Angat during the 2019 El Niño period.

This rise in temperature leads to rapid evaporation of surface water, leaving the soil dry and impacting its ability to store and release water to the reservoir.

Making matters worse, increased temperature triggers higher water consumption as people seek ways to cool down during the hot weather.

Rainfall in the water reservoir decreased by 9 out of 10 millimeters of rain per square meter during the first quarter of 2019 compared to the average rainfall recorded throughout the year. Angat Dam recorded zero to at most a liter of rainfall per square meter in the first four months of 2019, which could have triggered a decreased inflow to the water reservoir, thereby impacting its water level.

“The historical average inflow in Angat is 68 cubic meters per second, but during the dry season, it decreases to around 28-30 cubic meters per second. There were incidents when the inflow was less than 10 cubic meters per second,” said Mr. Bong Senadrin from the National Power Corporation (Napocor), which manages Angat water reservoir and is tasked with flood management to ensure dam safety.

During El Niño months, the water flowing into Angat Dam dropped dangerously during the past decade. The lowest average inflow of 27.7 cubic meters per second was recorded during the 2019 El Nino period, which equates to 6 cubic meters less for every 10 cubic meters of water flowing into the reservoir. This recorded inflow reduction is almost half of the 50 cubic meters that Metro Manila consumes each second.

According to Golda Hilario, Director for Urban Development at the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC), there is a significant correlation between El Niño and rising temperatures. She warned that this increase in temperature, even within the 1.5-degree threshold, would lead to an escalation in the intensity and frequency of El Niño occurrences in the coming years.

Over the past decade, the Philippines experienced three El Niño events. The longest of these lasted for 17 months, from February 2015 until June 2016, followed by another in 2019 from February until July. In July 2023, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) issued an El Niño Advisory, forecasting a strong El Niño expected to affect the country until the first half of 2024. The likelihood of below-normal rainfall conditions remains high, potentially leading to dry spells and drought and setting off another water crisis.

Hilario emphasized the need to address water security not only due to the threat of El Niño but also because of the growing population in Metro Manila. Coupled with the expansion of water services to adjacent areas of the metro, the increase in demand is inevitable. “As demand grows, finding new water sources becomes crucial. However, implementing infrastructure projects requires thorough planning and preparation. Solutions for such an urgent issue require immediate remediation; one cannot simply present a solution that would be available after 10 years,” she argued. In Part 3, we explore how the politics of water distribution blunt the call for immediate action.

Part 3: An Unequal City: Absorbing Metro Manila's Water Woes

While climate change, exacerbated by El Niño, contributed to the low water supply, Manila is a growing metropolis of haves and have nots with one of the highest rates of inequality in Southeast Asia. That inequality extends to who does and does not have access to water in good times and in bad.

Our analysis reveals that while wealthy areas consume more water in general, during water cuts, there is a lack of transparency around how decisions about where to allocate water were made and poorer communities were pushed to the edge of crisis in ways not experienced in wealthier areas.

On average, each resident in Metro Manila consumes 150 liters (40 gallons) of water daily. For every five bottles of water consumed by the average Metro Manila resident, Muntinlupa residents consumed only four while Makati residents consumed nearly seven.

Increased demand in Makati may be attributed to affluence, according to Patrick Ty from MWSS. People in Makati are wealthier and live in larger houses and well-equipped high-rise condos. Affluent individuals tend to consume more water individually, and the pools, gardens, and other amenities offered by these properties also contribute to the higher water usage.

“I am not entirely sure if it's really apples to apples because water consumption typically ranges between 150 and 170 lpcd (liters per capita per day). A value of 190 could be too high for domestic consumption. However, when considering possible reasons, it might be helpful to examine the preponderance of posh subdivisions, as they often have larger areas,” said Jeric Sevilla of Manila Water. He further explained that aside from the population growth rate of 2.2 percent, the influx of people reporting to work in the East Zone during the daytime could have also contributed to this consumption.

Based on the billed volume for Maynilad and Manila Water between 2017 and 2021, Metro Manila consumed an average of 1,300 million cubic meters of water per year, which equates to a daily consumption of nearly 4,000 million liters (MLD). Seven out of ten liters of water were utilized for domestic purposes, with the remaining three liters used under commercial, industrial, and semi-business classifications. Semi-business classifications refer to small businesses that do not rely on water as a fundamental part of their activities. Manufacturing, construction, transportation, and communication fall under industrial classifications, while other profit-oriented operations are considered commercial.

For every 50 liters utilized, an extra three liters were consumed from 2017 to 2022 as demand grew. Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a spike of one liter for every 10 liters consumed.

Water service connections also increased by almost half a million from 2018 to 2022. For every 20 existing connections, three new connections were established during those four years. While poorer areas consume less water even during the best of times, it is the decisions made about who does and does not get access to clean water during times of crisis that have some experts worried.

Who absorbs Metro Manila's water woes

In 2019, half of Metro Manila’s population was affected by cuts in water supply, with around 140,000 customers severely impacted or left without water for more than a week, according to MWSS. Other communities had to rely on water rationing either by the local government or through the two water concessionaires.

The problem arose from the decreasing water level in La Mesa Dam, which supplies water to Manila Water's East Zone customers. On March 4, 2019, they issued an advisory informing customers that certain areas would experience “low pressure to no water during peak demand.” This, according to news reports, triggered people to store water, exacerbating the already high water stress. La Mesa dipped to its critical level, prompting the service provider to suspend its releases and causing water shortages across Metro Manila. Despite cross-border releases from Maynilad, the supply remained insufficient.

“I remember when the water supply was cut off and didn't really know when it would come back. I had to travel from my home in Quezon City to my childhood home in Las Piñas (about 42 kilometers away). I brought empty containers and had to drive to my mother's place since they had water,” according to John (not his real name), who lives in a gated community in Barangay Pasong Tamo, Quezon City. "You only realize the value of something when it's gone. When the water shortage hit us, it was an equalizer, both rich and poor communities didn’t have a supply during that time" he added.

A Commission on Audit report on Water Services in Quezon City, published in August 2020, revealed that at least half of the respondents experienced interruptions in their tap water supply in 2019. Specifically, three out of every four Manila Water customers experienced at least one to four hours of water interruption.

In the Service Recovery Update released by Manila Water on June 22, 2019, Barangays Holy Spirit, Tandang Sora, and Pasong Tamo were identified as critical areas. The higher elevation of these barangays compared to the Balara Treatment plant resulted in low water pressure, leading to water supply cuts in the area and requiring the deployment of water tankers.

As La Mesa Dam's water level dipped to its critical level, in the East Zone, water usage dropped from two to eight liters in 2019 compared to the previous two years when Manila Water was forced to shut down service. In Parañaque, Manila Water customers consumed 8 liters less per day on average, marking the largest decrease among Metro Manila's highly urbanized cities and one independent municipality in 2019, based on the 2021 Water Demand Survey.

The decrease in Parañaque's water supply in 2019 was attributed to its distance from La Mesa Dam and the Balara water treatment plant. La Mesa Dam, serving as a buffer, is located approximately 35 kilometers away from Parañaque. Since water is distributed by gravity, areas farther from the source, particularly those in the south like Parañaque, became susceptible to supply issues when the water level in La Mesa Dam dropped. However, Maynilad consumers did not experience significant cuts since they were directly connected to Angat Dam.

Mandaluyong recorded 12 barangays where the entire population experienced severe water cuts, the highest number in the East Zone. In contrast, neighboring Makati was not listed as severely affected. Given its status as a central business district, Makati could have been given priority in water supply allocation. We investigated the reasons for Makati’s exclusion from the list of severely affected areas with Manila Water, but we have not yet received a response.

The 2019 incident also revealed that wealthier areas experience cuts as an inconvenience while poorer areas often experience the same cuts as a crisis due to the availability, or lack thereof, of other resources.

Water cuts are felt differently by different communities

Senior couple Vilma and Pampilo Eder, residents of Barangay Barangka in Mandaluyong recalled how difficult the situation was in 2019. Left alone during the day, Vilma had no other option but to line up for water during the peak of the heat when her kids and husband reported to work. She had to queue up again in the evening, often finishing in the early hours of the morning.

"It was very difficult. I told my family that I would not die from sickness but from standing in line for water, carrying and pulling all those containers under the scorching heat. At that time, I didn’t really get to rest, and my eating schedule was disrupted." Resting time was spent queuing up, which stretched for almost two kilometers with people waiting for their respective shares.

Disagreements arose among residents, and worse, grabbing of containers ensued as they struggled to secure their positions in the queue. Due to Pampilo’s disability, Vilma was left to fetch water for the household on her own. “I feel so sorry watching my wife carry containers of water filled from the trucks,” he said, describing how dire the situation was.

This scenario also highlights how gender issues arise, as it is typically women who are left with domestic chores like fetching water needed for cooking, bathing, laundry, and other activities requiring water use.

The Eder family had to wait for Manila Water's delivery since the water from the fire trucks was not potable. Water refilling stations also suspended their operations since there hadn't been any water from the tap for more than two weeks.

In an interview, Dr. Philamer Torio from the Ateneo School of Government explained how the 2019 water shortage exacerbated the existing inequities in water accessibility. Poorer communities, already struggling, had to allocate a larger portion of their income to secure water. According to his paper titled “Metro Manila’s 2019 Water Crisis: Of Efficiency Traps and Dry Taps,” those in the lowest socioeconomic class had to spend at least 5 to 10 percent of their income on water. Lower-income households suffer the most because they cannot easily afford alternative water supplies. Conversely, for those with better resources, the water shortages were merely a minor inconvenience.

In dire situations, inequality raised the stakes for certain families, according to John. He recounted witnessing a water truck delivering to a single household during the crisis. With no water, residents were initially relieved but later became disappointed when the water tank passed by without stopping. Residents confronted the delivery workers and lodged complaints with Manila Water. Subsequently, water delivery trucks were dispatched to the village. Water pressure also improved following the 2019 incident, after a water pump was installed in the village.

The government’s failure to forewarn and coordinate with local government units left communities unprepared for the impending water crisis, according to Golda Hilario of ICSC.

Regular updates could have equipped LGUs to prepare barangays for the looming crisis more effectively.

“The government fell short in holding water concessionaires accountable in meeting promised outputs, like 24/7 water supply and infrastructural development for sustainable water supply in Metro Manila,” added Prof. Vallejos from WPN. For the network, concessionaires, particularly Manila Water and Maynilad, need to invest in wastewater treatment facilities to reduce strain on our water resources, including recovery of wastewater to minimize demand for clean water from the Angat Dam.

As supply cuts were imposed due to the dwindling supply, rotational water distribution was implemented in affected communities. According to MWSS, residents in impacted areas were provided with a refund and a higher rebate of Php 2,500. John, residing in one of the severely affected barangays, recalls billing periods after the incident when they either weren't charged or had some amount deducted from their regular bill.

For others, access was not a major issue. “It wasn't really a big problem to the extent that I couldn't take a shower. There were times when I had to shower at the village sports club. I'm not sure why the club had water, but our membership gave us access to the facility, said John. “Drinking water also remained unaffected as our refilling station continued their service.”

Part 4: Quenching the thirst: new water sources, conservation and governance

Manila is going to be among a handful of cities in the world facing the biggest water scarcity crisis by 2050, according to a recent study published in Nature. Experts across the Philippines and the world have been sounding the alarm that the local government simply won’t be ready.

As climate change threatens water supplies, a larger percentage of the urban population may lose access unless governments act swiftly to secure water supplies. Instead of ambitious plans to increase supply, critics point to a focus on stopgap measures like reducing water loss due to leaks in the system.

PAGASA forecasts that 2024 may be the warmest year in the country's history due to the threat of El Niño. The public has been advised to conserve water and energy to prevent shortages, while the technical working group continues to monitor the situation. This emphasizes the need to enhance resource management to avoid a repeat of the 2019 crisis.

The Metro Manila Water Security Study, published in 2012 by the World Bank for MWSS, projects a high total water demand of nearly 5,000 MLD for Metro Manila by 2025. This projection takes into account the future targets of the concessionaires, including 150 liters per capita per day domestic water demand, commercial and industrial use, coverage of people to be served, and water losses.

“Twenty years later, the population being served is more than double, however, your source of water remains constant. And the major challenge here is you don’t build dams overnight. Additionally, we must consider the increasing urban development in Eastern Metro Manila, where there's a lot of vertical expansion—condominiums, tall buildings, and the like. So, the question arises: where are we going to get the water?” Sevilla asked.

The 2019 experience underscores the vulnerability of our water sources to climate change and extreme weather, exacerbated by growing population demands. For stakeholders and experts, better governance is imperative to help Metro Manila mitigate future threats.

Potential solutions include:

- diversifying water sources

- water conservation

- Regulating water use during good times and bad

- tariff reforms to discourage overconsumption

- Better oversight and regulation

“For all our basic needs, 95 percent of our water is addressed from Angat Dam. We are basically putting all our eggs in one basket. What if something happens to Angat? Let's say it goes below the min operating level, what if there’s an earthquake and aqueducts delivering water will be cut off?” Patrick Ty from MWSS said. “Then Metro Manila will be cut off from water. That's the reason why we are looking at new sources such as Kaliwa Dam. That’s the main focus of the corporate office.”

Securing additional water sources has been in the pipeline for decades, but solutions to address Metro Manila’s growing demand for water have not materialized, worsened by the lack of clarity on who should assume accountability. Existing water sources are shrinking due to climate change and the population is booming and thirsty. Improvements to water management that reduce water loss have put a bandaid on the problem and been used as an excuse to delay more ambitious plans to secure additional water sources.

Dr. Philamer Torio of the Ateneo School of Government said that many water security plans have been drafted but never translated from paper to water in the tap. He noted that the assumption was that new water sources would have been established within seven years from the date the concessionaires took over in 1997, but this never happened. He attributed the delay to the successful recovery of water lost through leaks and pilferage, which provided additional water supply in recent years. Manila Water has been able to cut its water losses or non-revenue water by half since taking over in 1997. Water loss of 1,000 MLD was reduced to 200 MLD in 2022, resulting in the production of an extra 800 MLD, equivalent to the output of a medium-sized dam.

Maynilad reported a 45 percent non-revenue water rate in 2021, out of the 2,400 MLD they received from Angat Dam. Cutting their 2021 water losses by a quarter in 2027 would entail recovering nearly 500 MLD from their supply. This is a drop in the bucket compared to future demand for water.

Diversifying Water Sources

Residents of Barangay Holy Spirit demonstrate that at least on a small scale, greater water resilience is possible. The barangay agriculturist, David Balilla, took the initiative to develop alternative water sources, which averted a crisis during the 2019 cuts. Aside from being serviced by Maynilad, Balilla installed a solar irrigation pump, which draws water from a deep well. He also explained that during water cuts, some residents lined up to fetch water at the “Gulayan and Bulaklakan Research Training Center.” Water from the center’s 2,000-liter rainwater harvesting facility was utilized to water plants and vegetables in their community’s urban farm. But Barangay Holy Spirit is an exception. The vast majority of people have no alternatives when the water is shut off.

After the 2019 water crisis, concessionaires were permitted to develop “short-term” and “medium-term” water sources to meet demand within 4 to 13 years. The development of “long-term” supply requirements, intended to provide water beyond 13 years, was left under the purview of the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS), as stipulated in the Concession Agreement.

MWSS has outlined a comprehensive “Water Source Roadmap,” which includes six different water sources that would provide a total of 4,658 million liters per day.

The identified short and medium-term sources in Cavite, Laguna, Wawa, and Pasay would augment an additional 20 percent to the existing water source by 2025.

The controversial Kaliwa Dam project is seen to supplement around 1,400 MLD by 2028. The Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS) also listed Kanan River Phase 2 as a potential source of 3,000 MLD of water by 2038.

These projects in Sierra Madre face staunch opposition from indigenous peoples and environmental groups, citing the project's impact on the Sierra Madre’s forest cover as well as the livelihoods of people dependent on the forest.

The WPN opposed the Kaliwa Dam project, advocating alternative solutions such as proper water management, rainwater catchment facilities, and greywater recycling. Rainwater harvesting, initially designed for households, can also be scaled up, utilizing spaces under flyovers or underground catchments, especially during monsoon seasons to mitigate flooding. Additionally, they recognize the potential for sustainably augmenting supply from Angat through water from Laguna Lake and rehabilitating existing dams.

The non-completion of the Laiban and Kaliwa Dam project can also be attributed to politics according to Dr. Torio. Everytime there’s a change in presidency, plans on how to build the needed water supply also changes. The dams were supposed to be funded through the Public-Private Partnership during the term of the late President Benigno Aquino, III but was scrapped after the Duterte Administration decided to finance the project through an Overseas Development Assistance from China. The project, targeted to operate by 2027, is currently at 23 percent completion, with tunnel boring ongoing from the outlet in Teresa, Rizal, as confirmed by the MWSS Corporate Office.

If finding a new water source is inevitable, the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities believes that projects should be approached with environmental sustainability in mind and with the involvement of the community hosting the project, ensuring that their concerns are properly addressed. For ICSC, “Indigenous groups should always be represented in the decision-making; their contribution should always be heard and should never be disregarded.” Furthermore, ICSC emphasizes the need to evaluate climate risk before giving the project a green light.

Water conservation: the cheaper solution

Taking into account the delays in establishing new water sources amid Metro Manila’s growing demand, water conservation becomes essential.

Water conservation proves to be a cheaper solution compared with the significant expenses involved in developing new water sources besides the considerable time required to complete such projects. “You can't build a dam overnight. It will take several years to develop these alternative water sources, which are expensive. So, the cheapest option really is to conserve water,” said Patrick Ty from MWSS, as he urged the public to participate in water conservation efforts.

Conservationists suggest a widespread public awareness campaign about practical water conservation steps. Jeric Sevilla from Manila Water suggests promoting wise and responsible water usage, regardless of the presence of El Niño or La Niña, or whether there’s plenty of water or none at all. “It has been an ethical issue that the water we use for flushing the toilet, drinking, and watering plants is all clean water,” said Sevilla.

Imagine using 4 to 7 liters of clean water, which could have been saved for drinking, to flush the toilet in one go. According to the Handbook of Water Use and Conservation, a person uses 70 liters of water daily for flushing when using a toilet without efficient fixtures. This amount could have covered a person's drinking water requirement for 23 days.

Greywater recycling and rainwater harvesting are among the potential solutions the local government of Quezon City included in their Local Climate Change Action Plan (LCCAP). Drawing lessons from the 2019 incident, Quezon City recognized water sufficiency as a critical issue that should be incorporated into the city's development plan.

To help alleviate Metro Manila’s growing need for water, greywater recycling is seen as a feasible solution to lessen the demand for raw water coming from Angat Dam. But this might require additional infrastructure or reengineering of plumbing systems if utilized for flushing and other non-drinking water needs.

While the full implementation of these solutions may take some time due to the required infrastructure development, their inclusion is a significant step that local government units could replicate to help address our water woes.

In 2022, Maynilad Water launched its New Water project, which recycles used water discharged from the concessionaire’s Paranaque Water Reclamation Facility. The project aims to produce 10 million liters of water daily, to be treated and blended with water from its La Mesa Treatment plant, for distribution as potable water to customers in Barangay San Isidro and San Dionisio in Paranaque City.

“How do you integrate water security into your development plan as a long-term strategy? If you cannot address it through infrastructure, we might want to approach it as a health issue. What's important is that you identify steps to address this significant concern,” said ICSC’s Hilario.

Regulating water use during good times and bad

Overconsumption should also be addressed through policy, according to experts. When the supply is short, demand management becomes a must, Dr. Torio said. Imposing restrictions on water usage when threats are present could extend the availability of water for a longer period. For example, Vancouver restricts residents from watering their lawn more than once a week during dry spells.

There’s a need to prioritize essential activities and operations. For example, in 2019, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management identified five hospitals in the National Capital Region affected by El Niño. It is crucial that facilities providing essential services are prioritized with water supply. Recreational activities should be given a lower priority in terms of consumption levels. There should be a balance in regulating activities that require water. For example, a public pool in Pasig City provides respite to numerous people as the heat index reaches dangerous levels of 40 degrees Celsius in some parts of the country. Residents cite how the water park helps seniors and children cope with the heat.

While individuals who consume more typically pay higher bills based on their usage, the increased cost is not a deterrent to higher consumption, given their ability to afford the bill, especially among wealthier households. To tackle overconsumption, Dr. Torio proposes tariff reforms to prevent users in affluent communities from consuming excessive amounts of water, especially during shortages.

“Economics also plays a role; a constant supply means profits for water providers, so they would avoid shutting off the supply. Concessionaires should agree to moderate the supply even if it means accepting a loss in profit,” said John. For him, conservation also boils down to mind conditioning. “It would be helpful to have water supply available for certain hours to encourage other people to conserve water," he explained.

Prof. Vallejos, spokesperson for the WPN, points out that overconsumption in affluent communities results from privatization, as those with the ability to pay more are seemingly given a free pass to consume more. This highlights the importance of governance. There should be policies regulating excessive consumption to ensure water availability for everyone, regardless of their social class. If water interruptions are imposed in low-income communities, the same approach should be implemented in affluent communities.

Better oversight and regulation

The creation of the Department of Water Resource Management is long overdue, according to Dr. Torio. Recognizing the challenges associated with water management, he believes that consolidating these tasks into one government agency would help address significant issues and speed up decision making. However, for the WPN, the proposed creation of the Department of Water is unnecessary, considering the existing number of institutions already working on and implementing regulations for water management. According to Prof. Vallejos, a careful review reveals that the proposal actually perpetuates privatization, as it would grant more power to the private sector. It seems to divest the government of control over our water resources and simply transfer the responsibility to the private sector.

The Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities also calls for better coordination among government agencies and stakeholders focused on water resource management. They view the lack of coordination among key players and the failure to assess and involve local government units as contributing factors to the problem, as observed in 2019.

The 2019 experience was a wake-up call for Manila Water. “We don’t want a repeat of the 2019 incident. That was an eye-opener for us; we cannot be too dependent on Angat. That is why we really need to look for additional water sources,” Sevilla said.

MWSS also committed to better monitoring of our water supply. "Yes, we will never go down to the same level again. The first is, we will not go below the operating level. If it goes below the operation level, we shut down, you cannot produce, you cannot keep on drawing water." according to Patrick Ty from MWSS.

“Access to affordable, quality, clean water is a basic human right, and the bulk of the responsibility in providing water lies with the government. That's a social contract because we pay taxes for government services," Hilario added.

“I hope we won't experience another water shortage like we did in 2019. It was really difficult for us,” said Vilma Eder. The Eder couple appeals to the government and the concessionaires for better management. “I just hope they would notify residents of possible water interruptions early on, maybe two weeks to a month in advance. This will give us enough time to prepare,” Vilma said.

According to the couple, the water supply was abruptly cut in 2019, which caused panic as they struggled to find alternative sources of water. “Water is essential. It sustains your strength, quenches your thirst. You can survive a day without food, but you can never survive without water,” noted Vilma.

HOW CAN YOU HELP?

-

According to MWSS, keeping the tap open while brushing your teeth utilizes 2 liters of water per 20 seconds. Using a cup when brushing is one way of helping to reduce wastage.

-

When washing hands, close the tap while lathering, then reopen it when rinsing.

-

Flushing the toilet requires 4 to 6 liters of water. People may opt to change their older toilets with fixtures with lower flush rates. Investing in newer technologies may be heavy on the pocket, some conservation groups recommend putting a brick or a bottle filled with water in the tank to lessen its capacity. However, plumbing organizations remind people to be careful, as this may affect the toilet's ability to flush waste effectively.

-

A person typically uses approximately 44 liters of water daily during showers. Remember to switch off the shower while lathering and reduce shower time. Also, be conscious of water usage when using water from the bucket.

-

Water used to wash fruits and vegetables may be utilized to water your plants instead of clean potable water.

-

Water utilized for washing clothes may also be used for flushing the toilet and cleaning. This would help reduce unnecessary consumption of clean water.

-

Use a basin when washing dishes. Grey water may be utilized to water plants.

-

Water your plants in the evening. Use a pail and dipper to limit water usage.

-

When eating out, only ask for water when needed. Advise your favorite restaurant to serve water only upon customers’ request.

-

Limit car washing schedules to once a week. Patronize car washing facilities that use grey water or other water-saving technologies.

(Source: Handbook of Water Use and Conservation- Investigations of the domestic water utilization in some cities in the USA).

Reporting for this story was supported by the Environmental Data Journalism Academy - a programme of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and Thibi.

EDITED BY Eva Constantaras, Jamaine Punzalan and Fernando G. Sepe Jr.

DATA VISUALIZATION Lumin Win, Thibi

ART AND GRAPHICS BY Pamela Denice Ramos

DEVELOPED BY Regie Francisco

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS Mark Demayo and Val Cuenca

PRODUCED BY Gigie Cruz

METHODOLOGY

The author utilized data on Angat Daily Reservoir Elevation from 2013 to 2023 obtained from 2 independent sources: the National Power Corporation (Napocor) and the National Water Resource Board (NWRB). The data from Napocor, which monitors inflows and releases as part of flood management, includes the Angat Reservoir Capacity Curve, based on bathymetric surveys conducted in 1994, 2008, and 2017, which was used to determine the change in Angat's water capacity when the water level drops to its drought zone.

Read moreRead less